Welcome to Acherontiscus

Name Definition

named after the mythical river Acheron

Name Given By

Robert Carroll in 1969

Location

Scotland, United Kingdom

Classification

Amphibia, Lepospondyli, Stegocephalia, Adelospondyli, Acherontiscidae (monogeneric or only has one genus)

Size

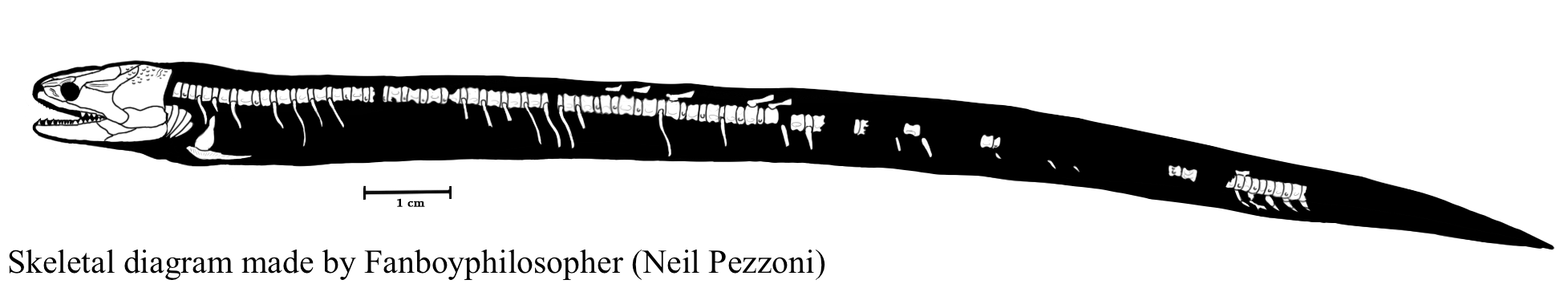

about 14 cm long (5.5 inches) though it may have been slightly longer since a portion of the tail is missing

Temporal Range

Late Visean - Middle Serpukhovian stages of the early Carboniferous, approximately 346 - 324 million years ago

Ecological niche

small aquatic durophage (a durophage is an animal that feeds on hard-shelled animals)

Species/Sub Species

A. caledoniae

Diet

given the deep jaw as well as the large and blunt dentition of the lower jaw, Acherontiscus would have most likely been a durophage and would have fed on molluscs, crustaceans, and ostracods (a kind of small crustacean)

Introduction

Acherontiscus is a genus of adelospondyl stem-tetrapods that lived in Scotland during the early Carboniferous. Acherontiscus was named after a river in Greek mythology called Acheron, and it was the river that flowed into the underworld and was also a tributary (a tributary is a river that flows into a larger river or lake) of the river called Styx (there is an elasmosaurid named after Styx called Styxosaurus). Naming Acherontiscus after a mythical river is also in reference to the fact that Edward C. Cope loved naming snake-like lepospondyls after mythical rivers, for example, the snake-like aïstopod Phlegethontia, which was named after mythical river Phlegethon, and the lysorophid amphibian Cocytinus, which was named after the river Cocytus, also known as Kokytos. The species name caledoniae is in reference to Caledonia, the Latin name for Scotland which is where Acherontiscus was found. Acherontiscus is only known from one mostly complete but poorly preserved skeleton which consists of a compressed skull that was partially eroded on the surface, some vertebrae, and detailed impressions of missing vertebrae.

Acherontiscus, through phylogenetic analysis, has been found to be an adelospondyl, an order of aquatic amphibians that superficially resemble snakes. Adelospondyls are traditionally included in the subclass Lepospondyli because they, like most lepospondyls, have fused vertebrae, though Acherontiscus is an exception. However, some studies in 2007 have objected to this claim and do not interpret adelospondyls are lepospondyls. Instead, they consider adelospondyls as close relatives or even members of the family Colosteidae, a family of primitive stegocephalians. If the counter-argument is correct, then this means that adelospondyls would have evolved before the tetrapods split into reptiles and modern-day amphibians, as colosteids are stem-tetrapods, and this would mean that they are intermediate between the earliest terrestrial vertebrates such as Ichthyostega and they are the ancestors of all the groups ancestral to later tetrapods which includes temnospondyls, as well as all modern day vertebrates such as reptiles, mammals, birds, and amphibians.

Overall, Acherontiscus was like a snake, and had an elongated body with a proportionately small head. What’s even more interesting is that legs may have been absent on Acherontiscus since there is a lack of preserved limb bones from the single skeleton. While this hypothesis has been taken into account, Acherontiscus most likely had limbed ancestors which makes it possible that a dermal shoulder girdle was present on Acherontiscus, so if Acherontiscus did possess limbs, they would have been very puny and small and wouldn’t have accounted for much bone material in the entire skeleton. Acherontiscus was small compared to modern-day amphibians and was only 14 cm long, however it may have been slightly longer since a part of the tail is missing.

Due to the presence of a lateral line on Acherontiscus, it was most likely an aquatic animal. Lateral lines are a visible line present on modern day fish and fully aquatic amphibians that consist of a series of sensory organs which detect pressure changes and vibrations in the water. This is especially helpful for orientation and helps the animal gain more information about their surroundings. Another piece of evidence that Acherontiscus virtually lived their entire lives in water is the fact that either Acherontiscus would have had very reduced limbs or no limbs, making life on land more difficult than in the water. To move in the water, Acherontiscus would have moved in a lateral undulation similar to those of snakes, and this movement would have been facilitated by its serpentine form and the embolomerous vertebrae it possessed. This would have been a good adaptation for moving around obstacles to find food. Due to the relatively large hyoid apparatus (the hyoid apparatus is a series of bones that support the tongue and larynx, also known as the voice box) present in Acherontiscus, it has been suggested that Acherontiscus had gills in life, though they were most likely internal gills in the skin like modern-day fish rather than external frill-like gills like neotenic salamanders such as the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). Taking into account the blunt and robust teeth of the lower jaw in Acherontiscus, Acherontiscus was probably a durophage, an animal that eats smaller animals with a hard shell or exoskeleton. It would have preyed on aquatic molluscs, crustaceans, and ostracods, a group of very small crustaceans, and were common in the rock slab that preserved the specimen of Acherontiscus. The relatively deep jaw also supports this durophagy hypothesis since it would have given Acherontiscus a hard bite to crack open the shells of invertebrates, a necessary adaptation for durophages. Acherontiscus is the earliest animal in the fossil record with heterodont dentition (a heterodont animal is an animal with different forms of teeth in its mouth) and predates the recently discovered captorhinid reptile Opisthodontosaurus carrolli by about 50 million years.